History

An Education for Freedom

The Program of Liberal Studies was a child of the “Great Books” movement of the 1920s-60s. Especially following the rise of totalitarianism, many Americans hoped that peaceful and free democracies could be secured by a return to basic principles of citizenship and justice that had supported democratic ideals from Ancient Greece to the founding of the United States. To this end, Great Books programs began to proliferate across the nation. From early origins at Columbia University, the University of Chicago, and St. John’s College, it was not long until many colleges across the nation had their own Great Books Program.

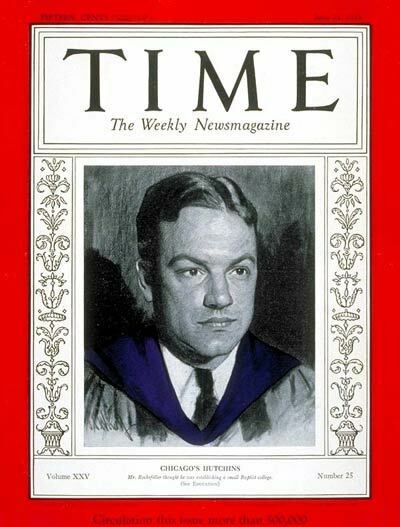

The expansion of interest in Great Books was originally motivated by the conviction that freedom of the mind is essential for political freedom. As Robert Hutchins, president and then chancellor of University of Chicago from 1929-51, wrote in his 1943 book Education for Freedom, “The liberal arts are the arts of freedom. To be free [one] must understand the tradition in which [one] lives. […] We want minds that are free because they understand the order of goods and can achieve them in their order. The proper task of education is the production of such minds.” Because, as Hutchins goes on to say, “most of the great books of the world were written for ordinary people, not for professors alone,” such an education was to be achieved not through indoctrination by expert lecturers, but through the seminar discussion method, which was radically egalitarian and not open to the power of a single authority to lead the group astray.

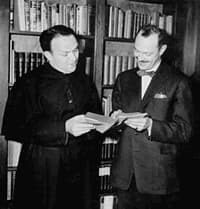

This radical new style of learning appealed to Notre Dame President John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., and in 1947 the first Great Books seminars were held at Notre Dame. These seminars were led by Judge Roger Kiley, a Notre Dame alumnus and distinguished appellate judge in Chicago, in addition to President Cavanaugh. At first, the seminars were only available to select law students, but eventually all first- and second-year law students were required to take these seminars. Thus, the first Notre Dame Great Books seminar found its home in the law school.

Those first years were not without difficulty. The program faced many critics from Catholic leaders and parishes across the nation. The concern was over the wisdom of encouraging Catholics to read a syllabus of books assembled without concern for creed or ecclesiastical authority—indeed, many of the texts that appeared in the first Great Books canon had been placed on the Vatican’s “Index of Forbidden Books.” For Notre Dame students at the time, books on the Index were locked in a metal grill enclosure, and students could access them only with the University President’s permission, which was delegated to him from the bishop of the diocese.

It would seem then, that the Great Books program of Notre Dame was doomed from the start. A program at a Catholic University receiving heavy criticism from lay Catholics and clergy across the nation does not appear to have much of a future. President Cavanaugh, however, believed strongly that Notre Dame students should read and discuss the most powerful and important texts from both within and outside the Catholic intellectual tradition.

During several years of his presidency, Cavanaugh served on the Board of directors of the Great Books Foundation of Chicago. When asked for a statement of the purpose of the Great Books movement, John Cavanaugh wrote, “The Great Books that contain the great ideas are most helpful in any Twentieth Century attempt at liberal and general education, not only because they help lead minds to think, but also because they help lead minds to think about the basic aspects of the problems of the human community. Experience shows that liberal and general education for adults ordinarily can best be carried on with the aid of Great Books.” It was only through the deep love and appreciation that President Cavanaugh had for Great Books that the Program was able to make it out of its infancy and into the next part of its life: undergraduate studies.

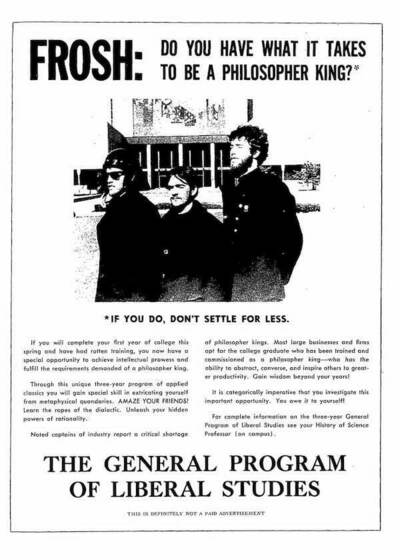

In 1950, the Great Books made their debut as an undergraduate course of study in the College of Arts and Letters as the “General Program of Liberal Education” under the leadership of Professor Otto Bird. It opened with a faculty of five, forty-nine students, and a canon that, with some modifications particular to its being embedded in a self-consciously Catholic university, followed the Great Books of the Western World canon edited by University of Chicago professor Mortimer Adler and published by Encyclopedia Britannica.

The Program was a new and different course of studies than any that had been followed at Notre Dame. The primary aim of the Program was to give students an understanding of the broadly Western culture in which they found themselves and, through this understanding, to develop the critical thinking skills needed to live a free intellectual and practical life. Its secondary interest was to place this culture in dialogue with the philosophical and theological principles of the Catholic intellectual tradition.

The Program was intentionally set up as a pilot curriculum to help chart a course for the future of the university. It may have been the hope of President Cavanaugh that the Program would eventually be adopted for the whole college, but this would never come to pass. The Program did, however, transform the general approach to teaching a learning across Notre Dame.

First, students throughout the University began to read more primary texts. Before the Program, students would generally only learn about major authors and their ideas through textbooks. With the introduction of the General Program, students and faculty were compelled to read and teach the foundational works of their academic disciplines by engaging in the interpretive struggle to understand ideas in the words of their authors.

Secondly, the Program’s style of teaching was centered around class discussion and empowered students to speak their minds, testing their interpretations of difficult texts and wrestling with complex ideas in conversation with their peers. This new way of teaching was incredibly effective as a mode of learning and popular with students who had grown tired of being expected to passively receive the information that their professors sought to communicate through lectures. In the fall of 1956, a discussion-based study of classic texts, the Collegiate Seminar, became a requirement for all students in the College of Arts and Letters.

Lastly, before 1950, the university had virtually no policy for inviting specialists from outside the university to present to students. Because of this lack, the Program began a weekly lecture series, eventually leading to the development of Notre Dame’s own special lecture series.

For these reasons and more, the Program shaped the overall fabric of liberal arts education at Notre Dame. And, in the years following, the Program itself would continue to evolve in conversation with the University and the world.

In 1954, Notre Dame created the First Year of Studies program. Now, instead of four years to traverse the Great Books, students would only have three. This led to the elimination of the language tutorials (Latin and French), two years of mathematics training, and a shortening of the science curriculum. It was through these changes, however, that the Program was able to better find its identity.

With the addition of a shared First Year curriculum, students could more readily take electives outside of the Program and thereby develop specializations and concentrations that they would not have been able to pursue otherwise. By combining a core intellectual foundation from PLS with specialized courses from other departments, students could benefit from a rich liberal arts education while also taking full advantage of the resources of a research university.

Over the next fifty years, the Program would experience many changes as the world changed around it. In 1972, Mary Celeste Amato would become the first woman to graduate from the Program. The 1970s also saw a steady increase in enrollment and a name change. Instead of the General Program of Liberal Studies, the Great Books at Notre Dame became just the Program of Liberal Studies (though many alumni retain their loyalty to the GP title!). During this period, the Program began expanding the scope of its curriculum, becoming the first of the major American “great books” programs to include texts from ancient China and India as part of its core Seminars.

By the late twentieth century, PLS was attracting attention on a national level. Louis Dupre of Yale noted that PLS was “the best Great Books program” in the nation, and Thomas Roche of Princeton said that PLS was “one of the most interesting education programs in America.”

Such national recognition would not be possible without the strong alumni network that PLS proudly exhibits. The unique sense of community fostered on campus was strong enough to be felt even after students graduated. From our founding to now, students who study PLS remember it for the rest of their lives and continue to pursue that same liberal education long after graduating. Many participate in alumni reading groups or return to campus for our annual alumni Summer Symposium.

Today, the students and faculty of PLS remain committed to the ideal of liberal education as education for freedom. Such freedom requires disciplining and expanding the intellect, but also learning from those who have come before. To be truly educated, as the philosopher Cornel West has said recently, “means to find your voice, not an echo or an imitation of others. But you can’t find your voice without being grounded in tradition, grounded in legacies, grounded in heritages.” Through wide-ranging Seminar discussions, focused disciplinary training in tutorials, and a lively intellectual and social community, the Program of Liberal Studies continues to explore powerful and important texts from the past as a way to enrich our understanding of the present and to foster a vibrant and just democracy.

Compiled with the help of Mark Mehochko, PLS '23

For a more complete history, please see the following materials gathered in the 2000-2001 academic year to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Program:

- January 2001 Programma (50th Anniversary Issue)

- 50th Anniversary Conference Proceedings (April 2001) Part I and Part II

- PLS: The First Fifty Years