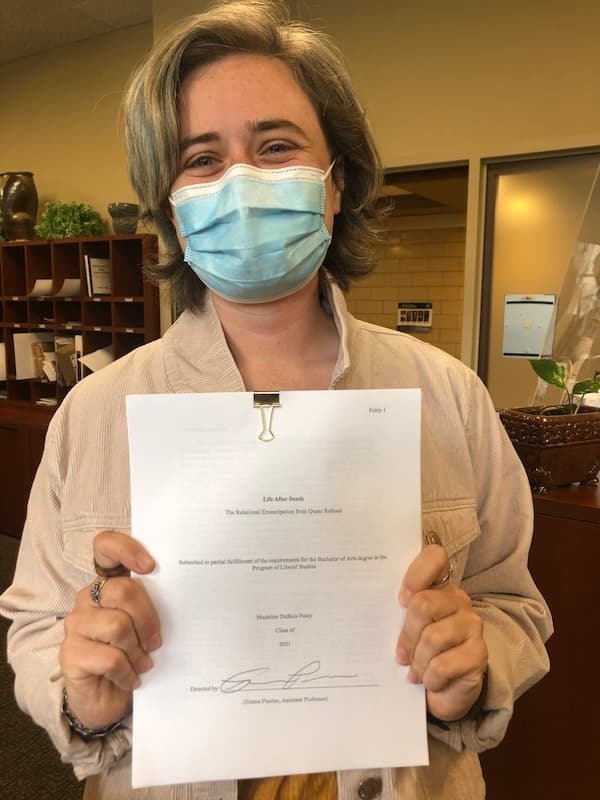

Madeline Foley, PLS '21, won the Otto A. Bird award for 2021, which recognizes the best senior thesis written in the Program of Liberal Studies for that year. Her thesis was titled, "Life After Death: The Relational Emancipation from Queer Refusal." To mark the occasion, Maddie spoke with us about the process of writing the thesis and her plans for the future.

"I felt that my thesis connected, in an interdisciplinary way, my life experience of the past four years in the Program while also critically engaging with the present moment of the pandemic and all of the difficult questions that that experience raised. Such a project could only be tremendously rewarding."

1. What is the topic of your thesis, and why did you choose to research and write on this?

I began developing ideas for my thesis as a result of my experiences as a queer Catholic. I spent the past several years reading Christian apologetics, biblical interpretation, and queer theology to understand first whether or not I could be included in the Christian church and secondly whether or not the question of “inclusion” was the right question at all. I began reading Marcella Althaus-Reid and Linn Tonstad, two queer theologians. The first worked to continually expand the boundaries of what we consider “holy,” inverting our conceptions of the profane and the indecent until we come to recognize that the act of shattering concepts like “decency” is itself holy. The second is most famous for her argument that “inclusion” is misguided; simply welcoming marginalized people into oppressive structures does nothing to change those structures.

With these theorists in mind, I set out to write a philosophical and theological interpretation of Lee Edelman’s book No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. I found his work compelling because of its radicality: Lee Edelman pulls no punches and is quite explicit at points in his ire against nationalism, religion, and even children. Edelman argues that every single effort to be included or even be understood by society or the political sphere becomes co-opted by violent narratives; the only option, therefore, is an absolute refusal to participate in political visions, fight for a “better future,” or even be understood by one’s fellow human beings. He’s considered the founder of the “antisocial thesis” in queer theory, for perhaps obvious reasons.

However, I began to suspect that Edelman's description of the human person, which relies heavily on Lacanian psychoanalysis, did not, in fact, have to be strictly anti-relational. Because I had a vested interest in relationality— the concept that human beings depend on each other both in body and mind— and radical queer theology, I wanted to write a theory that (to the best of my ability) didn’t uphold any oppressive worldviews while also maintaining the idea that we can be related to each other. I argued that human beings have an ethical responsibility to refuse being understood, because any and all conceptions— or judgments, or discourse in the Symbolic-Imaginary, whatever you prefer— do violence to human beings because the core of the human being is meaninglessness. This meaninglessness is both caused and illuminated by the presence of an Other; the relationality comes in at that point. I argued that queer refusal takes the form of an act of Self-dissolving love. Under the current circumstances of oppression, this act results in an embrace of death for the life of the Other, since the Other is the cause of one’s own life.

2. What did you expect to find when you started your research, and how did your views evolve as you got into the project?

When I started my research, I thought I was going to write about Rousseau as the foundation for queer theory! I was onto something, I think, since I was primarily fascinated by the complicated duality of isolation and relationality in the human condition. I ended up focusing more on critical theory and modern philosophy, which were both topics I hadn’t chronologically begun learning yet through the Program. I was also surprised by how long I stayed with Edelman. When I began my thesis, I thought he was just troublesome and controversial— and his book was incredibly hard. By the end, I realized that underneath his more contextual writing was a firm philosophical backbone which helped me formulate the argument of my thesis.

3. What was the most challenging part of the thesis process, and what was the most rewarding? (Other than winning the Bird award!)

I think one of the most challenging aspects of the thesis process was figuring out what genre or field an undergraduate thesis “fits” in. I wrote a very interdisciplinary thesis, which was rewarding because it enabled me to synthesize lots of threads that I had been exploring during my time in PLS and at Notre Dame. In the beginning, though, I was just reading book after book and essay after essay in quarantine, taking notes and trying to imagine what direction I would eventually explore. Another challenging aspect was writing this thesis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of course, there were many logistical and mental health issues that arose for everyone during the pandemic. However, the thesis process was the most rewarding way I could have spent the pandemic year. In order to responsibly protect the health of my community, I was already spending a lot of time alone. I was able to do so while reading and writing about topics that carried great personal weight. Luckily, writing my thesis during the pandemic felt less like a burden and more like a slow and steady attempt to process everything that I, along with everyone, was going through. Not everyone’s thesis has emotional weight or is the “capstone” of their college experience, and that is totally okay— for some people, it’s better, because it takes some pressure off. But I believe that doing a more personal thesis was exactly what I needed during the pandemic. I felt that my thesis connected, in an interdisciplinary way, my life experience of the past four years in the Program while also critically engaging with the present moment of the pandemic and all of the difficult questions that that experience raised. Such a project could only be tremendously rewarding.

4. What did you discover about your topic and yourself during this process that surprised you or unsettled you or affirmed you?

I was deeply affirmed by re-discovering my own passion and love for learning in general. High school and college have structures which often incline students to complete coursework because it is required, or because the student is looking for good grades or a good resumé. The thesis process does not work like that. There are deadlines, but to complete the project you have to be self-motivated from the beginning to the end. It's a marathon, not a sprint, and it was very moving to see my own thinking and writing skills improve over time. There were definitely bumps in the road: my draft from the fall semester was returned to me with particularly devastating comments. I knew that I trusted my advisor, and I wasn’t going to give up, so I sat down and began editing before even meeting with her. I had to cut up my thesis with scissors several times just to get it in the right order. Putting together all the moving parts felt a little bit like walking a tightrope; I wasn’t sure until the very end that the argument would actually “work,” which was admittedly a little nerve-wracking. Being able to read through the finished product and know how far I had come from that moment was an incredibly affirming experience.

5. What are you doing after graduation, and how will the work that you did on your thesis inform your future work and life?

After graduation, I’m doing a service year with the Episcopal Service Corps in Tucson, Arizona. I believe that working on my thesis developed skills of patience, determination, and humility, which will serve me well in that capacity. I also think that the topic of my thesis and the ideas contained in the works I read for research have helped and will continue to help me to better love other people in all of their differences, complications, and contradictions. Talking about my thesis with other people and incorporating their advice made me a better listener, while helping edit other people’s theses in working groups helped me be a better writer and even a better friend.

Writing the thesis implanted a permanent love of learning in me as well as a willingness and capacity to have my own thoughts continually challenged. Because of PLS and the senior thesis, I plan to pursue an academic career while striving to always remember that inquiry, knowledge, and reason itself should always be used to liberate human life rather than hinder it.